Why most car dealers still don’t have any electric vehicles

Electric cars and trucks are more popular than ever, and sales are growing, but if you want one, you’ll probably have a hard time finding an EV in stock near you.

Two-thirds of US car dealers surveyed in a new Sierra Club study, published Monday, didn’t have any battery electric or plug-in hybrids for sale in 2022, new or used.

“There are more dealerships that have electric vehicles since the last time we did this report [in 2019], but it’s still shockingly low,” said Katherine García, director of the Clean Transportation for All Campaign at the Sierra Club.

Transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US, with passenger cars and trucks making up 57 percent of this share. So electrifying sedans, SUVs, and pickups is an essential component of the strategy for meeting climate change targets. The US has committed to cutting its total emissions in half from 2005 levels by 2030. Meanwhile, automakers like General Motors have committed to going all-electric, and there are looming bans on fossil fuel-powered cars in some of the largest car-buying states like California and New York.

So what’s the holdup?

A big part of it is due to supply chain blockages, with shortfalls in semiconductor and battery production preventing manufacturers from making enough electrics to meet demand. Some of the largest carmakers in the world — Honda, Toyota, Stellantis — had few if any EVs and plug-in hybrid models at all for sale in North America last year. According to the Sierra Club survey, 44 percent of car dealers who didn’t have an EV on their lots would gladly sell them if they could get their hands on one.

“The larger bottleneck is with the manufacturers themselves,” García said.

But 45 percent of dealers without EVs said they wouldn’t sell them even if they were available. The structure of the car sales model can put dealers, manufacturers, and customers at odds since the economics of EVs can disrupt the business model for dealerships. It’s another critical choke point: If a dealer is resistant to stocking electric cars and trucks, a buyer might not have any nearby options for the specific EV they want since manufacturers grant dealers monopolies in a given area.

With the rise of all-electric carmakers like Tesla and Rivian, however, there’s a push for car companies to sell their vehicles directly to customers without the middleman. It’s forcing major auto companies and dealers to adapt and it will chart the route ahead for zero-emissions cars and trucks.

Why car dealers matter so much for electric cars and trucks

The EV buying experience varies a lot depending on what kind of car you’re looking for and where you are. Ninety percent of Mercedes-Benz dealers had an EV for sale compared to 11 percent of Honda retailers, according to the Sierra Club study. This includes used vehicles for sale that were made by another manufacturer.

Your best bet for finding an EV on the lot was in the southeastern US in states like Georgia and Florida, where 41 percent of dealers had an electric for sale. In Western states like California, Oregon, and Washington, only 27 percent of dealers had EVs in stock. This region also accounted for 45 percent of EV sales in the US, so the lower stock was likely due to more demand.

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24639723/GettyImages_1238020766.jpeg)

A Ford dealership in Richmond, California. The state has the highest EV sales in the country. Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images – Fetch from vox.com

Some manufacturers are racing to keep up while also coping with recalls. Dealers in turn are adjusting to these sporadic supplies, but also trying to accommodate how EVs are changing the way they do business.

All states have rules that encourage or require carmakers to sell vehicles to customers through dealerships. There are close to 17,000 franchise new car dealers in the US, and they sold 13.7 million light-duty vehicles last year, according to the National Automobile Dealers Association.

Originally, these regulations were designed to prevent a handful of major car companies from colluding across the country and fixing prices. Dealers also expanded the footprint of carmakers and gave buyers a local point of contact. They’re technically independent franchises, which means that they can set their own prices and incentives, but carmakers have a lot of leverage in how dealerships function.

Vivek Astvansh, an assistant professor of marketing at Indiana University, explained that car dealers have three main functions: They sell cars and take trade-ins on behalf of the manufacturer, they provide loans to buyers, and they perform maintenance and repairs.

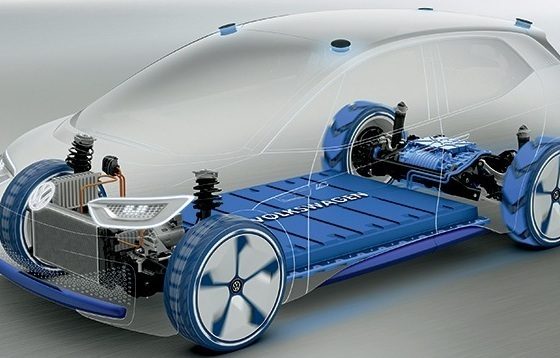

It turns out that parts and service can account for nearly half of a dealership’s profits. But EVs don’t need oil changes, spark plugs, or valve checks. “All else equal, an electric car has fewer mechanical parts than a gasoline or diesel car, which directly means that the revenue a car dealer makes from an electric car is much lower than what the dealer will make from a gas or diesel counterpart,” said Astvansh.

If there are any issues or recalls, many fixes for EVs can be applied over the air rather than going to a dealer. It’s a selling point for an EV buyer but a challenge for a dealer. “That is why they are hesitant to make a strong case for electric cars,” Astvansh said.

On the other hand, many people are buying EVs for the first time and they’re counting on dealers to teach them the ins and outs of charging, maximizing range, and taking advantage of government incentives. As cars have become less mechanical, they’ve become more computerized, creating a learning curve for first-time drivers who may not appreciate the importance of keeping their car’s software updated, for example.

“The foremost function that a dealer can provide is that of educating the buyers,” Astvansh said. “Customers cannot just use ChatGPT or Google and have all the information. They need to interact with a human being.”

But dealers have to make investments in their infrastructure to sell EVs. Ford has created an EV certification program for its dealers, which requires them to build fast chargers and train their staff to work on electrics. The top-tier certification can cost a dealership up to $1.2 million to achieve, but it gives them first crack at new EVs and allocates them more inventory. Ford said that more than half of Ford dealers in the US have signed on as the company aims to build its own EV charging network.

“It’s good for Ford; it’s just that the initial investment is expensive,” said Devron Stevenson, general manager of Banister Ford of Marlow Heights in Maryland. Stevenson said his dealership is gearing up to install level 3 fast chargers this year that can top up an EV in minutes, but require dedicated grid connections and specialized electrical hardware.

Similarly, General Motors, the parent company of Chevrolet, is enacting standards for dealers. “For EVs, dealers must maintain the proper service tools, battery charging equipment, and training, as well as meeting customer experience standards,” said David Caldwell, a spokesperson for GM. “More than 90 percent of Chevrolet dealers are enrolled.”

But even if manufacturers build them and dealers sell them, the trickier question is whether enough people will buy electric cars and trucks to make this all worthwhile. With borrowing costs increasing, EVs are a tougher sell since on average they have a higher sticker price than their fossil fuel counterparts. Earlier this month, Ford announced a price cut of up to 8 percent on its Mustang Mach-E. For dealers, how much they invest in EV infrastructure now is a delicate balancing act. “It’s going to depend: How fast can we get them? Can we afford them? Does it make sense overall in the next 24 months? To me, it’s a bit of a toss-up,” Stevenson said.

What if you want to avoid the dealer altogether?

Dealer franchise laws across the US benefit existing dealers but pose a problem for manufacturers that want to sell directly to their customers in some states. Tesla operates a factory in Texas, but the company can’t sell its cars to Texans directly. The cars have to be shipped out of the state before delivery to a Texas buyer.

Other EV-only carmakers like Rivian and Lucid also sell directly to consumers. This doesn’t factor into the Sierra Club’s calculations, so EVs are more accessible to more people than the number of cars on lots lets on.

EV companies say that this direct-to-consumer model lets them elide the haggling of traditional car dealers and avoid the costs of maintaining dealer lots and sales staff. Twenty-three states now allow direct sales for EV-only auto companies, though they they still face restrictions in many cases. Several more states are working on laws to make direct sales easier, either by relaxing rules or granting EV makers dealer licenses.

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24636481/GettyImages_1232968450.jpeg)

The Biden administration proposed new fuel economy rules that would require two-thirds of cars sold to be electric by 2032. Nicholas Kamm/AFP via Getty Images – fetch from vox.com

Conventional automakers like Ford and Volkswagen have recently started to echo this, letting customers buy cars online and pick them up at a dealer rather than going through the sales process in person.

Yet even EVs need to have their tires rotated, and all-electric companies are rushing to build out service centers to handle maintenance and recalls, or leaning on traditional automakers. “How important is convenient local service to customers? Since 2021, Tesla owners have come to GM dealerships for service on more than 11,000 occasions,” Caldwell said.

He added that while EVs may not yet be available everywhere, the auto industry is making the largest and fastest technological change in its history. In 2020, electric cars and trucks accounted for 4.2 percent of new vehicle sales worldwide. In 2021, 8.3 percent. Last year, 14 percent.

“Two words: It’s happening,” Caldwell said.

Source : vox.com